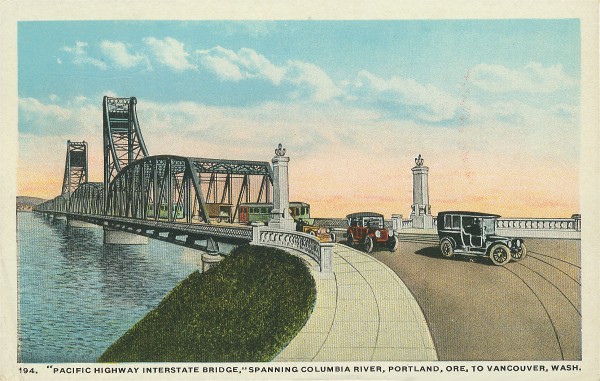

The original (East bridge) incorporated trolley tracks. The bridge is consequently heavier and has larger counter-weights on the lift section. The original northbound bridge weighs about a third more than the newer one.

Vancouver’s interstate bridge assembly yard built the bridge sections which were then ferried into place.

In the 1920s, Jantzen Knitting Mills built the 112-acre Jantzen Beach Amusement Park as a promotion for Jantzen swimming suits. It had swimming pools, roller coasters, ballrooms, and the C.W. Parker merry-go-round.

Attractions like the Jantzen Beach Amusement Park, Oaks Park, and the Council Crest Amusement Park also worked as promotions for Portland Streetcars. In 1970, the Jantzen Beach Park closed its doors, the buildings were demolished, and the site redeveloped into the Jantzen Beach Center Mall.

The Interstate Bridge has been found to have significant seismic vulnerabilities and would collapse or be rendered unusable in an earthquake, according to ODOT’s Seismic Report on bridges. Bruce Johnson, state bridge engineer for the O-DOT, says of the Interstate Bridge, “I’m confident that it would collapse under a 9.0 earthquake”.

The lift span on the older (eastern) bridge has a cracked trunnion, an axle pulley that will cost as much as $12 million to fix in a few years, reports The Oregonian. A 10-man Oregon crew currently maintains and operates the bridge, headed by bridge supervisor Marc Gross. Bridge tenders on Gross’s crew man the drawbridge controls around the clock, performing about 400 lifts a year.

The Vancouver streetcar was owned by Portland Railway, Light and Power Company (now PGE). It carried passengers from Vancouver WA, across the Columbia River (via the interstate bridge) to Hayden Island where it split into two directions. One line continued south towards downtown Portland.

The other line veered diagonally, southeast across the North Portland harbor over a 1700 foot long wooden trestle and stopped at a station known as Faloma on the Oregon shore, the gateway to the Lotus Isle resort. The Tomahawk Island bridge crossed North Portland Harbor.

You can still see the RR bridge pilings near Lotus Isle Park.

The city park is located on what was once called Sand Island. The 1938 map (below) shows the still separated “Sand Island” where the Lotus Isle Amusement Park was located.

Sand Island was later renamed Tomahawk Island (after someone found a tomahawk), and eventually merged with Hayden Island with infill when the I-5 freeway was built in the 1960s. Hayden Island Drive was originally constructed in the early 1970s, and was rebuilt in the mid 1980s due to settlement failure.

Hayden Island has held a series of names. It was first recorded as Menzies Island in 1792 by British Lt. Broughton. Lewis and Clark called it “Image Canoe Island” in 1905 for an impressively carved canoe they encountered while camping there. Finally it was renamed for Guy Hayden, an early mayor of Vancouver who owned a farm on the island. Hi-Noon has additional history of the island.

The Columbia River Railroad Bridge, about a mile West of the Interstate Bridge, is owned and operated by BNSF Railway. Completed in 1908, it was the first bridge of any kind to be built across the lower Columbia River. It preceded the nearby Interstate Bridge by almost nine years. The same RR bridge remains in use today.

Abraham Lincoln signed the Northern Pacific Charter in 1864 with the charge of constructing a rail connection between the Great Lakes and Puget Sound. In 1873 the Northern Pacific announced that Tacoma, Washington would be the railroad’s terminus on Puget Sound and scheduled service began between Kalama and Tacoma in January 1874.

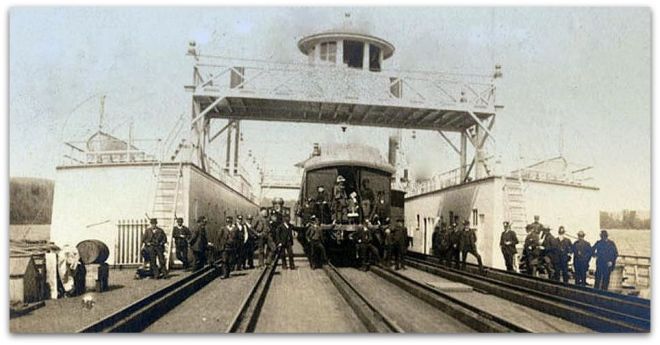

Before the 1908 Railroad Bridge in Portland, the Northern Pacific built a railroad ferry that connected the Port of Kalama on the Washington side to Goble Oregon, just east of Longview/Rainier. Passenger service continued until 1934.

The Goble train ferry began in 1884 and continued until 1908 (when the Portland RR bridge was completed). The mighty Tacoma was built in Delaware but disassembled, boxed and shipped off to Oregon. Some 57,159 separate pieces were brought out from New York by the Tillie E. Starbuck, the first iron sailing vessel built in the United States, and reassembled in Portland to build the train ferry.

The Pacific Northwest Rail Corridor is one of eleven federally designated high-speed rail corridors in the United States. The 466-mile corridor extends from Eugene, Oregon to Vancouver, British Columbia via Portland and Seattle.

The recent 600-ft wide, 43-ft deep navigation channel terminates at the Interstate Bridge. The I-5 bridges were designed with an assumed life of 50 years. But average bridge life in Oregon is 85 years. According to state officials, 1,500 Oregon bridges will reach the end of their service life by 2020.

Some say the I-5 bridge is haunted by the ghost of Vancouver Mayor Percival who may – or may not – have taken his life shortly after the bridge was dedicated. “The story goes that people will be driving across the bridge at night, and they’ll see this tall, slender man walking in period clothing,” according to Brad Richardson, a historian and volunteer services coordinator with the Clark County Historical Museum. “It’s always on fall nights, and it’s always on the old (parts) of the bridge.”

The Vancouver Waterfront Project will span most of the vacant land between the Interstate 5 Bridge, top, and the BNSF Railway bridge.

Today the Interstate Bridge is congested, routinely backing up traffic for miles. More than 125,000 vehicles cross the I-5/Columbia River bridge, daily.

Here are 360 degree photos of the I-5 bridge on Flickr. Click on them to see “VR” panoramas.

Columbia River Crossing would have replaced the obsolete four-lane Interstate 5 bridge with a new 12-lane bridge and light-rail extension over the Columbia River. That project, 10 years in planning, is now officially dead. Here’s a Bloomberg story on our (non-happening) bridge.

Portland-Vancouver drivers can anticipate almost 10 hours of congested travel a day by 2020, compared to a total of four hours of congested travel today. Because the Port of Portland lost their container shipping business on Terminal 6, additional truck traffic is also expected. Approximately $40 billion in freight crosses the I-5 bridge annually.

The existing freeway would have been replaced by a 17-lane behemoth, 45-feet high and 450-feet-wide.

CRC planners initially drew up a fixed span with just 95 feet of clearance over the Columbia River. That height was rejected by the U.S. Coast Guard and others as inadequate for the navigation and economic needs of river users. Here’s the Coast Guard Statement of Facts.

The project was subsequently redesigned to a height of 116 feet, and riverfront companies harmed by a 116-foot span made mitigation deals with the CRC.

Most of the I-5 congestion is on the Oregon side but largely caused by Vancouver commuters. Washington didn’t want to pay for Oregon road work. A lack of cooperation and common courtesy killed it.

Portlanders say many ‘Couverites use Oregon roads and parks, then drive home to their Clark County homes, paying no Oregon taxes or Washington state income tax’. Clark County’s population nearly doubled from 238,000 in 1990 to more than 400,000 today.

CRC detractors said the light rail component should be removed. They believed Tri-Met would siphon business away from the downtown area to the sales tax free haven on Jantzen Beach and Portland.

CRC supporters said the $850 million in federal transit funding was a necessary component. Never mind that Light Rail would likely have given a big boost for Vancouver’s Waterfront project and probably the city’s economy.

The project was considered dead after Washington lawmakers failed to fund their $450 million share of the $3.4B project in June, 2013, but became undead when it was resuscitated under an Oregon-financed initiative, supported by Governor Kitzaber.

Under the revised Oregon-led finance plan the project budget was estimated to be approximately $2.71 billion. A summary of project revenues is provided (above). Tolls were supposed to cover the $1.9 billion Oregon would have to borrow to build the project — a risk the state would have to bear alone.

But it was largely all for naught. Or so it would seem.

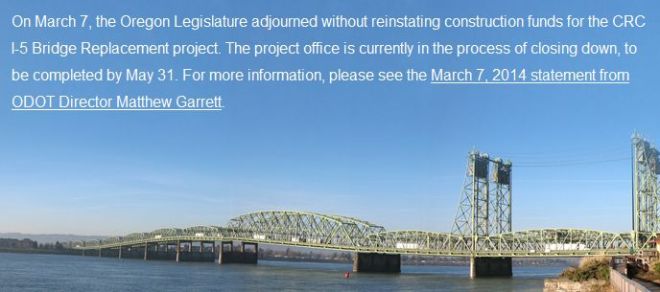

Columbia River Crossing died a quiet death when, in March, 2014, the Oregon Legislature took no action to keep it going. CRC obituraries are available from the Vancouver Columbian and the Portland Oregonian. The Columbia River Crossing project after more than a decade of work and nearly $190 million in planning, was officially declared dead by the Oregon Department of Transportation in March, 2014.

The Oregon Department of Transportation in 2014 closed the I-5 bridge project’s offices, issued cease-work orders to its many contractors and shut the project down entirely by May 31, 2014.

The Bi-State Bridge Coalition met for the first time in June, 2014, soon after the final collapse of the Columbia River Crossing. The group is led by Clark County Republicans who played a central role in killing off the CRC. Vancouver’s new mayor, Anne McEnerny-Ogle, is for a new I-5 bridge.

The 24-member Portland Region Value Pricing Policy Advisory Committee will consider Oregon’s plan for tolling on interstates 5 and 205, as outlined in the state’s $5.3 billion transportation funding package.

Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler (R-Battle Ground, WA), has been adamantly outspoken against tolling and any plans to do so. She also successfully sponsored an amendment in a federal spending bill to prevent Oregon from spending federal funding to implement tolls on interstates in 2018.

One option could incorporate other ideas such as renovating the rail bridge downstream from the I-5 bridge to reduce congestion on I-5, and the possibility of a west side bypass bridge.

One approach could incorporate other ideas such as renovating the rail bridge downstream from the I-5 bridge to reduce congestion on I-5, and the possibility of a west side bypass bridge.

Another (new) proposal for an East County Bridge was championed by ex-Clark County Commissioner Dave Madore, an outspoken opponent of the Columbia River Crossing.

At an estimated $860 million, Madore says a third bridge is a common sense approach to relieving congestion. A fatal CRC flaw, in Madore’s view, was the project’s inclusion of light rail.

His bridge would would connect with SR-14 in Washington, but on the Oregon side it would connect to nothing. It would be located about a mile EAST of the 205 bridge. It would have little impact on current I-5 congestion.

Vancouver Mayor Tim Leavitt called it a “bogus bridge”. It’s hard to see how Madore’s bridge will be God’s gift to East County.

The Planning and Sustainability Commission chose the environment over jobs, reports the Portland Tribune. The 2035 Comprehensive Plan Update incorporates The Transportation System Plan (TSP), a 20 year plan to guide transportation investments in Portland.

Portland’s 20-year comprehensive plan map shows it is betting everything on being able to make car-lite transportation dramatically more attractive than it is now.

Portland’s Transportation System Plan (TSP) is aligned with Metro’s Regional Transportation Plan. These comprehensive documents are backed by lots of studies and research.

Oregon legislature in 2017 passed a $5.3 billion transportation package in July 2017, the most comprehensive transportation bill that the Oregon legislature has ever passed.

House Bill 2017, would raise the gas tax by 4 cents in 2018 and then gradually add another 6 cents. Vehicle fees would also increase and there would be another new tax of 0.5 percent on new vehicle sales.

Transit improvements would be funded by a 0.1 percent payroll tax on workers. There would also be additional funding for bicycle and pedestrian paths — and the bill would impose a $15 fee on the sale of adult bicycles that cost at least $200.

Three major Metro-area projects are set up for funding under the plan, and will be funded in part with rush-hour tolls. It would add lanes to Interstate 5 through the Rose Quarter and add lanes to Interstate 205.

Tolls could be an important part of helping to pay for the Portland freeway work, particularly the project to add a lane in each direction on I-205 from the Abernethy Bridge to Stafford Road around Oregon City.

Columbia River Crossing Links:

- Wikipedia: Interstate I-5 Bridge

- Wikipedia: Columbia River Crossing

- ColumbiaRiverCrossing.org

- Oregon Dept of Transportation: CRC

- WS-DOT: CRC

- WA Governor: CRC

- CRCfacts.info

- StopCRC.com

- Oregon Live

- Vancouver Columbian

- Willamette Week

- Bike Portland

- Bike Portland: Common Sense Alternative

- Portland Afoot: Common Sense Alternative

- Dave Madore’s Proposed East County Bridge

- Vintage Portland

- ODOT’s Seismic Report on bridges

Current Columbia River bridge traffic (per day):

- Interstate Bridge 124,000

- Glenn Jackson Bridge 139,000

This Multnomah County page shows the ‘realtime’ status of bridges being open or closed. Portland’s 10 bridges spanning the Willamette River carry 540,000 vehicles per day between them.

- Sellwood 30,000

- Ross Island 55,000

- Marquam 138,000

- Hawthorne 30,000

- Morrison 50,000

- Burnside 40,000

- Steel 25,000

- Broadway 30,000

- Fremont 118,000

- St Johns 23,000

Soon, our cars will drive themselves. That much is clear. Bridges built for cars made in the previous century will not serve needs of the population even ten years in the future.

Here’s an alternative proposal to reduce congestion. Autonomous shuttles could connect Vancouver to the Yellow Line and completely bypasses freeway congestion. Self driving vehicles will arrive before a new bridge. Plan on it.

A small, dedicated bridge for autonomous cars, bikes and pedestrians may off-load congestion – providing a light rail alternative without any new light rail.